Facts, Theories and Perspectives in Psychology

Pre-reading 1

SOURCE:

Burton, Lorelle J. (2018). Psychology, 5th Australian and New Zealand Edition. Wiley.

Reading Part 1

What is an elephant?

A tale is told of several blind men in India who came upon an elephant. They had no knowledge of what an elephant was and, eager to understand the beast, they reached out to explore it. One man grabbed its trunk and concluded, ‘An elephant is like a snake’. Another touched its ear and proclaimed, ‘An elephant is like a leaf’. A third, examining its leg, disagreed: ‘An elephant’, he announced, ‘is like the trunk of a tree.’

Psychologists are in some ways like those blind men, struggling with imperfect instruments to try to understand the beast we call human nature, and typically touching only part of the animal while trying to grasp the whole. So why do we not just look at ‘the facts’, instead of relying on perspectives that lead us to grasp only the trunk or the tail? Because we are cognitively incapable of seeing reality without imposing some kind of order on what otherwise seems like chaos.

SOURCE:

Burton, Lorelle J. (2018). Psychology, 5th Australian and New Zealand Edition. Wiley.

Pre-reading 2

Consider the following questions before going on to read further:

1) Why is perspective imporatant?

1) How does perspective relate to psychology?

2) Is perspective objective or subjective?

SOURCE:

Burton, Lorelle J. (2018). Psychology, 5th Australian and New Zealand Edition. Wiley.

Reading Part 2

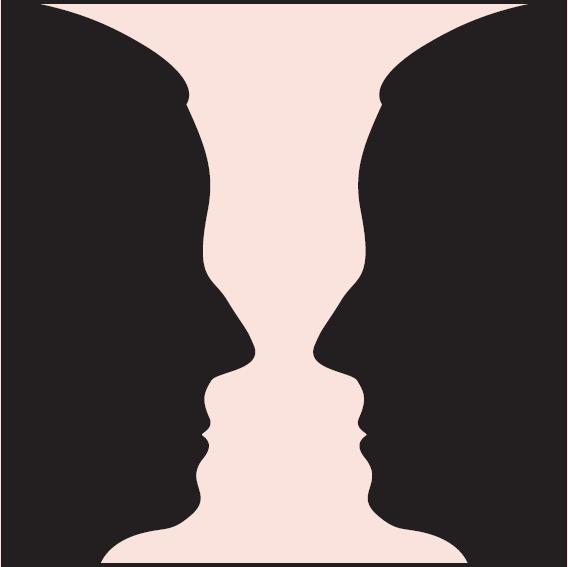

The importance of perspective can be illustrated by a simple perceptual phenomenon. Consider the figure below. Does it depict a vase? The profiles of two faces? The answer depends on your perspective on the whole picture. Were we not to impose some perspective on this figure, we would see nothing but patches of black and white.

This picture was used by a German school of psychology in the early twentieth century, known as Gestalt psychology. The Gestalt psychologists argued that perception is not a passive experience akin to taking photographic snapshots. Rather, perception is an active experience of imposing order on an overwhelming panorama of details by seeing them as parts of larger wholes (or gestalts).

SOURCE:

Burton, Lorelle J. (2018). Psychology, 5th Australian and New Zealand Edition. Wiley.

Pre-reading 3

SOURCE:

Burton, Lorelle J. (2018). Psychology, 5th Australian and New Zealand Edition. Wiley.

Conclusion

To take a clinical example (an example from the therapeutic practice of psychology), a patient with an irrational fear, or phobia, of elevators is told by one psychologist that her problem stems from the way thoughts and feelings were connected in her mind as a child. A second psychologist informs her that her problem is a result of an unfortunate connection between something in her environment, an elevator, and her learned response — avoidance of elevators. A third — examining the data, no less — concludes that she has faulty wiring in her brain that leads to irrational anxiety.

What can we make of this state of affairs, in which experts disagree on the meaning and implications of a simple symptom? And what confidence could anyone have in seeking psychological help? The alternative is even less attractive: a psychologist with no perspective at all would be totally baffled and could only recommend to this patient that she take the stairs. Perspectives are like imperfect lenses through which we view some aspect of reality. Often they are too convex or too concave, leaving their wearers blind to data on the periphery of their understanding. Without them, however, we are totally blind.

SOURCE:

Burton, Lorelle J. (2018). Psychology, 5th Australian and New Zealand Edition. Wiley.